Our last article1 focused on the upcoming requirements from the November 2021 New York State Department of Financial Services (NY DFS) climate change guidance regarding governance and organizational structure. Now that we’ve offered best practices as to how insurers might meet those requirements, let’s begin to examine how a well-governed and well-structured insurer can build a lasting enterprise risk management (ERM) framework to address climate change risk.

An ERM process for addressing changing climate risk should follow these commonly accepted steps:

In this article, we will focus largely on the identification of risk, specifically the physical risks involved in the underwriting processes conducted by U.S. property and casualty (P&C) insurance companies. We will also tee up more discussion of the assessment and measurement of risk for future articles. Discussion of scenario analysis, mitigation, and monitoring and disclosure will also be left for subsequent articles. Note that the underwriting risks are interrelated with other risks (e.g., asset, economic, operational, etc.), and those connections will also be explored in future articles.

There are two main categories of physical risk: acute and chronic.

- Acute risks are short-term, event-driven risks such as hurricanes, windstorms, tropical cyclones, earthquakes, severe convective storms, tornadoes, derechos, floods, winter storms, extreme freezes, and wildfires.

- Chronic risks (e.g., heat wave, rising sea level, and drought) manifest themselves as a result of longer-term climate changes.

For all acute risks (excluding earthquake) and one chronic risk (drought) noted above, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides a database of peril counts and costs for all U.S. disasters by year since the 1980s that have exceeded $1 billion on a consumer price index (CPI)-adjusted basis.2 Based on the available data, we note the following trends in frequency and severity of these climate events.

Events

- Severe storms are the most prevalent disaster and have increased consistently and dramatically across the decades, particularly in the 2010s.

- Flooding events were also particularly high in the 2010s.

- Tropical cyclones and wildfires have become persistent events in the last two to three decades.

- The total number of inflation-adjusted $1 billion disasters in the United States have increased from 29 in the 1980s (or about three per year) to 123 (or about one per month) in the 2010s.

Figure 1: Disaster count by decade

| DISASTER COUNT | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

| SEVERE STORM | 7 | 14 | 27 | 71 |

| FLOODING | 4 | 8 | 3 | 18 |

| TROPICAL CYCLONE | 6 | 12 | 15 | 12 |

| DROUGHT | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| WILDFIRE | 0 | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| WINTER STORM | 3 | 8 | 1 | 6 |

| FREEZE | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 29 | 53 | 63 | 123 |

Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2022)

Costs

- Disaster costs for tropical cyclones are by far the costliest and have been increasing rapidly across the decades. By implication, the severity of these storms is the driver of these increases.

- Severe storm costs, the second-largest cost, have also increased dramatically across the decades.

- Wildfire costs nearly doubled between the 1990s and 2000s, and then tripled over the next decade.

- The total costs across all inflation-adjusted $1 billion disasters in the United States have increased from $190 billion in the 1980s to $873 billion in the 2010s, or an average increase of 66% per decade.

Figure 2: Disaster costs by decade ($ billions)

| DISASTER COUNT | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

| TROPICAL CYCLONE | 40.9 | 112.9 | 396.1 | 475.8 |

| SEVERE STORM | 9.5 | 34.3 | 60.1 | 170.6 |

| DROUGHT | 103.7 | 24.0 | 59.3 | 84.7 |

| FLOODING | 15.0 | 64.7 | 16.7 | 65.2 |

| WILDFIRE | 0.0 | 10.9 | 18.7 | 62.4 |

| WINTER STORM | 5.8 | 34.5 | 1.2 | 13.1 |

| FREEZE | 15.3 | 11.7 | 4.7 | 1.1 |

| TOTAL | 190.2 | 293.0 | 556.8 | 872.9 |

Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2022)

Changes in overall cost distribution

- Between the 1980s and the 2010s, tropical cyclones and severe storms have increased their share of total costs from approximately 25% to 75%.

Figure 3: Changes in cost, 1980s and 2010s

Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2022)

Higher exposure means higher costs

The increases in loss frequency and costs are also directly related to increases in exposure to loss. In other words, development of properties and infrastructure in hazardous areas has contributed to this increased loss trend. The increase in exposure is largely driven by two forces:

- Expansion: Development of formerly undeveloped land, which includes more people moving to the coastal areas.

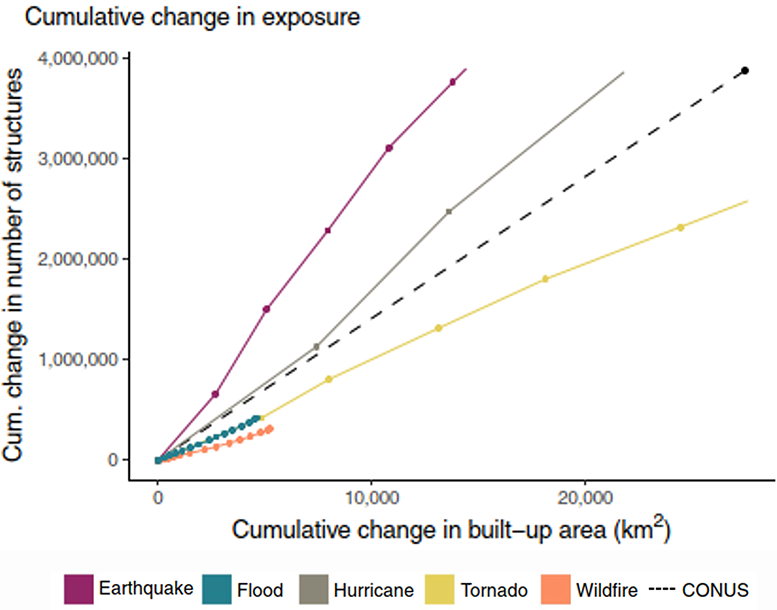

- Densification: Addition of new structures to previously developed areas. Per the graph in Figure 4, increases in cumulative exposure (i.e., number of structures relative to built-up area) have been highest for hurricane, earthquake, and tornadoes.3 (Note: CONUS = conterminous United States.)

Figure 4: Cumulative changes in exposure

Source: Iglesias, V., Braswell, A.E., Rossi, M. W., Joseph, M. B., McShane, C., Cattau, M., et al. (2021). Risky development: Increasing exposure to natural hazards in the United States, Earth’s Future, 9, e202EF001795. AGU, Advancing Earth and Space Science.

These trends have been building for decades and are an ominous signal for insurers. In response, insurers certainly have multiple strategic business options, from actively seeking to write these risks and employing advanced risk mitigation strategies, to outright avoidance. It should be noted that, since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the insurance industry has increasingly worked with insureds to improve building codes, materials used, etc., to better withstand and mitigate damages due to earthquake, hurricanes, and other perils. However, recent signs of market failure (e.g., availability crisis for both Florida homeowners and California wildfire coverage) are likely leading indicators that progress made over the last 30 years is insufficient. Without a renewed working partnership between policyholder and insurer, climate costs will seemingly increase unabated. Thus, based on the above charts and market impacts, a clear call to action exists once again for insurers—for the benefit of policyholders and other constituents, insurers need to specifically push for underwriting and/or cost reduction solutions to lessen the impact of the increasing trends in claims costs and exposure to loss in hazardous areas.

What should insurers do?

Before a company can think about assessing its underwriting risk appetite in light of climate change risks, it must seek to further understand these risks. We recommend the following action items in setting up a long-lasting framework to understand and measure the underwriting, and hence the pricing, of physical climate risks.

- Engaging outside climate experts to assist in understanding how climate change’s impacts are being analyzed, modeled, and mitigated, and how these activities are integrated into risk strategy.

- Engaging a catastrophe modeling firm to provide specific company estimates of losses by peril, both at expected levels and at various higher probability levels. This will set a baseline onto which assessments specific to climate change risk can be added.

- Monitoring applicable regulatory jurisdictions to assess whether your company can withstand the impact of potentially increased regulation (e.g., moratoriums on nonrenewals, etc.).

- Monitoring the effects of federal and state legislation on renewable energy alternatives and emissions reporting requirements to determine the potential impact on your desired underwriting profile.

We note that a key part of the risk identification process is to assess materiality of these risks. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Financial Condition Examiners Handbook provides some guidance as follows:

- Quantitative: Greater than 5% of surplus or one-half of 1% of total assets.

- Qualitative: When a risk rises to a level where it could influence the decisions or judgment of an insurer’s relevant stakeholders.

The increased attention that climate change has received in the insurance industry is de facto evidence that it can influence the decisions of the insurer’s stakeholders. Regardless of approach, a materiality standard should be established, and risks should be assessed against it at least annually.

Once an insurer has identified these risks, understood them, and measured their materiality, the next step should be to determine the company's appetite for these risks. That is an assessment process—evaluating the exposure to these identified climate risks. It is best practice from a strategic standpoint for companies to have a written risk appetite statement, and how an insurer manages material climate risks should be worked into this statement. Insurers should determine that offering a product is viable (i.e., within its risk appetite). If not, insurers should consider whether risk mitigation factors could resolve this and still allow for product viability. While setting risk appetite statements can often be a difficult, time-consuming task, especially so when the risks are not yet fully understood, they allow for strategic guide rails to be set in the underwriting process.

The assessment process will likely be a combination of qualitative and quantitative efforts. While a qualitative assessment may be based on simple “what if” models and a small set of risk factors, a quantitative assessment should seek to quantify those risks based on increasingly sophisticated tools like geospatial data and climate modeling.

While we focused this article on physical risks in P&C underwriting, insurers should ultimately assess climate change factors across a broader set of relevant risk factors, including those described in the Handbook (i.e., credit, legal, liquidity, market, operational, reputational, and strategic risks). The mapping of climate change risks to these risk exposures, and scenario analyses that consider the pathways through which these risks may evolve, will be the subject of future articles.

1 DiCenso, S.R. (February 8, 2022). Climate Change Governance and Strategy Requirements: How Might New York Insurers Comply With Them. Milliman Insight. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/climate-change-governance-and-strategy-requirements-how-might-new-york-insurers-comply-with-them.

2 NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2022). https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/billions/, DOI: 10.25921/stkw-7w73.

3 Iglesias, V., Braswell, A. E., Rossi, M. W., Joseph, M. B., McShane, C., Cattau, M., et al. (2021). Risky development: Increasing exposure to natural hazards in the United States. Earth's Future, 9, e2020EF001795. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF001795.